20th Century Philosopher, 21st Century Philosophy

A Short Essay on Francis Parker Yockey's Ideas of History and Civilization

Introduction

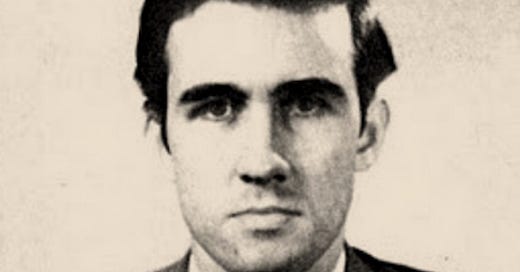

For my Philosophy course in college I was tasked on writing an essay on a figure of my choice in which I would give an explanation of their ideals. Naturally, I chose Francis Parker Yockey, who was one of my first inspirations when I first delved into Fascist and National Socialist ideology, and he still remains one of my primary influences to this day. The essay is rather short, and I don’t go into as much detail as I would have liked, but it got a 9/10 from my teacher so that instills a slight confidence in its quality. As such, I just wanted to post it here to act as a filler before my review of Hitler’s Revolution is complete, so please enjoy at your leisure.

The Essay Proper

Francis Parker Yockey bases his theories of history, most notably the evolution of civilization, on the writings of Oswald Spengler, while also synthesizing these writings with Fascist philosophy to create his own worldview. The 20th century was a time represented by monumental conflicts such as two World Wars, as well as the Cold War. However, this turbulent time should not only be seen as a battle between bullets and bayonets, but also of ideology. To a casual observer, the fall of Monarchy and subsequent rise of Liberalism, as well as the explosion of Fascism and Communism onto the world could be seen as a part of a greater cycle that all developed civilizations go through. Figures like Spengler and Yockey fit firmly into the latter, as they chose to interpret history and culture in a cyclical fashion, while applying Hegelian Dialectics to these concepts in order to clearly map out how these cultural changes would occur. This approach stands in opposition to what one could call “Left Hegelians” such as Marx, who famously used Hegelian Dialectics to envision a progressive interpretation of history as opposed to a cyclical one. Yockey’s philosophy is a synthesis in and of itself, one that deserves a great amount of observation and analysis, as well as a good amount of credit for truly standing on its own amongst the Pandora’s Box of ideologies that was opened after WWI.

In his literary magnum opus Imperium, Yockey lays out his philosophy in great detail across 567 pages. One can make out an interesting synthesis of different previous philosophers in Yockey’s ideals, most notably Spengler, Hegel, and Nietzsche, while also retaining some of Yockey’s Catholic faith as well. However, all these different influences revolve around three principal aspects to his worldview: History, Culture, and Politics. How Yockey defines these three ideological pillars is imperative to understanding his worldview as a whole. It is worth noting that there are even unique elements to Yockey’s writing style, in which he exhibits various quirks. These quirks include the combining of various terms into one concept, an example being Culture Distorter being written as Culture-Distorter or writing the names of people he dislikes in all lowercase letters. For the sake of brevity, these quirks will be replicated as necessary.

History is surely a complicated subject, as one could see by just how many people have written about different ways to structure history in general, or to analyze its events. Yockey defines History in a way that is deceptively simple: “What then, is History? History is the relationship between the Past and the Present. Because the Present is constantly changing, so is History.”[1] With this approach, Yockey ultimately splits History into two different aspects of itself, the Subjective and Objective. These two aspects serve as a way to lay out both how people choose to analyze history, as well as structure it for scholarly and educational purposes. The Subjective aspect of history is based around the ability of any one individual who tries to look at history in one way or another. “Men are thus differentiated also with regard to their capacity for understanding History. There is a historical sense, which can see behind the surface of history to the soul that is the determinant of this history.”[2] What Yockey means by this is that because different individuals have different intellectual strengths and weaknesses, they will inevitably see History from many different perspectives, with these individuals forming their own opinions on historical events that take into effect their own limitations, biases, and prejudices. Thus, history itself takes on a certain subjective nature. But the question presents itself: If history is subjective according to each person’s own view on it, how do we interpret history on a scale larger than the individual? The answer to this question lies within the second aspect of History: The Objective.

Yockey’s definition of Objective History is also a bit more complicated than one would assume if observed at face value. Yockey acknowledges that this aspect is as incapable of rigid establishment, but that “it inevitably selects and orders the facts…”[3] What he is effectively saying is that while Objective History is in fact more solid and organized than Subjective History, it is still beholden to “the poetic intuition, historical sense, and flair of the author”[4] as Yockey puts it. Without these personal touches, a history book becomes nothing but a collection of dates and names, which Yockey disregards as history-writing. This is because Yockey does not envision History as a simple timeline of events to be jotted down or recorded, but as an organic phenomenon which constantly grows alongside our discovery of new facts or perspectives on various historical matters. As we discover more about various historical figures or events, our perspective on them naturally changes over time. However, until every fact is uncovered, some artistic license is often necessary to fill in the gaps. This serves to imbue a certain spirit in historical accounts, a soul of sorts which also ties back into Subjective History.

As such, Yockey likes to define History as observing and analyzing the relationship between Subjective and Objective History. However, Yockey’s analysis of History is not contrasting the two Aspects against one another but using them as thesis and antithesis in a Hegelian Dialectic. The goal is not for one to overcome the other, but for the two to be observed together as a synthesis. This creates an entirely new concept to observe, as Yockey describes, “Each of the Two Aspects can be arbitrary, but the relationship is not arbitrary, but is the expression of the Spirit of the Age, and is therefore true, historically speaking.”[5]

It is in the concept of the Spirit of the Age that we find the bedrock of Yockey. He defines the Spirit of the Age as a collective feeling that permeates each aspect of society for a time, before giving way to a new one. A similar term that describes the same phenomenon would be zeitgeist. While a progressive would naturally view History as a linear affair, Yockey follows Spengler in viewing it as cyclical, with each stage of the cycle being defined by the Spirit of the Age. Yockey defines the Spirit of each Age rather abstractly, which coincides with his analysis of History in general, but each Spirit can be defined by the prevailing feeling in each Life-Phase of a civilization which are “The religious feeling that is uppermost in the first great Life-Phase, which is then superseded by the critical, which is then to be succeeded by the historical outlook, which gradually merges again into the rebirth of religion.”[6]

Spengler also observed this cycle, but while Yockey exhibits the stages of History by their Spirit, Spengler instead used his own concept of Forms. A form is defined as a historical recurrence that arises naturally in the minds of men and also dies just as naturally to a new Form.

“It is, and always has been, a matter of knowledge that the expression-forms of world-history are limited in number, and that eras, epochs, situations, and persons are ever repeating themselves true to type.”[7]

Spengler specifically likes to use the Forms of historical figures to indicate the passing of an Age. Most famously was his archetype of the Caesar figure, who served as the one to put an end to corruption and decadence in a society and usher in a time of order and authority. Spengler lists Napoleon and Fredrick the Great as two examples of Caesar figures in Decline of the West, but he also points out how Napoleon compared himself to Charlamagne, as well as how Caesar himself is often compared to Alexander the Great. To Spengler, it is a sort of natural desire for us to compare great men to historical archetypes represented by previous great men, and in this we see the creation of one of Spengler’s Forms.

Between these two men, Spengler and Yockey, we see many similarities, which only makes sense as Yockey obviously borrows from Spengler who serves as his main inspiration. However, the two also possess some differences as well, which mainly stem from their political differences. Spengler was a reactionary and a pessimist, so his cycle of Forms ended not in a glorious rebirth, but a disastrous collapse that would then lead to a rebirth if conditions allowed for it. Yockey differed from Spengler in that he was a Fascist, and thus an Idealist. For Yockey, the so-called end of the cycle would not lead to collapse, but to a revivalism of culture and a Return of Religion. This is evident by laying out the overall Spirit that defines each of Yockey’s stages of civilization: Faith, Skepticism, and then Will. In his Twentieth-Century Metaphysics, Yockey defines the Spirit of the Age of Will as “the true is that which I feel, the good is that which I want, the beautiful is that which pleases me.”[8]

In observing the Spirit of Will as Yockey puts it, his influences from Fascism are clear. Will was a central concept in every branch of Fascism that arose out of the ashes of WWI, and became Fascism’s main weapon against the ineffectiveness and timidness of Democracy. Whereas Democracy was busy either questioning everything, as in Yockey’s eyes Democracy embodied the Spirit of Skepticism, or with pointless arguing, Fascism had the Will to stride forward and commit to action in order to carve out a new Era. This will also embody Fascism’s opposition to the principles of the Enlightenment, and was also evident with many Fascist movements, primarily the NSDAP in Germany, associating with art forms like Romanticism, which presented a nostalgia for the past and an emphasis on emotion and passion over reason.

Both because of its opposition to the Enlightenment as well as its focus on feeling and order, Yockey identified Fascism as that which would facilitate the end of the Age of Skepticism and bring about the Age of Absolute Politics and the Return of Religion. It would seem that Yockey was not incorrect in his assessment, as Fascism’s national nature, traditional leanings, and opposition to Communism and Liberalism led to it forming bonds with religious institutions, and effectively led to a renewal of religious vigor. Mussolini notably comments on the natural alliance between his Italian Fascist state and the Catholic Church in The Doctrine of Fascism: “In the Fascist State religion is considered one of the deepest manifestations of the spirit of man; thus, it is not only respected but defended and protected.”[9] We see here the continued emphasis on the spirit of man, as opposed to the focus on the rational mind that Liberalism often places.

While Yockey may only differ from Spengler in trifling matters, he stands staunchly opposed to what he considers to be the lingering remnants of the 19th Century, which he calls the Century of Rationalism. These are primarily defined as the philosophies of Marxism, Darwinism, and Freudism. In Yockey’s eyes, while these outlooks were appropriate to the Spirit of the Age in the previous century, their materialistic and over-analytic views served only to corrupt and hinder the new Spirit, that being Will. Yockey also personally saw these philosophies as insulting to the human spirit, as he described their materialistic tendencies as “To Marx, the world is a huge moneybag; to Freud it is a dung heap; to Darwin a zoo.”[10] Each of these worldviews seek to lower Man to some dismal state in which he can be viewed as a mode of production, or a mere product of nature, or a beast ultimately controlled by his sexual desires, and as such they are irrelevant in the coming Age of Wil, which Yockey characterizes as possessing the qualities of faith, piety, heroism, and an adaptation of Nietzschean Vitality.

For the simplest contrast, we see Yockey’s idea of an organic, multifaceted, ever-growing and cycling History stand opposed to one Francis Fukuyama. Francis Fukuyama was a man who witnessed the collapse of the USSR in 1991 and reacted by declaring the End of History. In Fukuyama’s eyes, the defeat of Communism served as a sign that the political world had reached its apex in the political form of Liberal Democracy, accompanied by the economic form of Free-Market Capitalism. As a result of this “End of History”, there would be no more development in either of these fields, as humanity had reached a metaphorical peak. While Fukuyama was proven wrong on September 11th, 2001 when a new resurgence in terrorism revealed that the peace that accompanied the world post-USSR was indeed fragile, it is worth noting that Fukuyama did not exist in a vacuum. Francis Fukuyama was simply taking the static, linear interpretation of History to its natural conclusion from the point of view of political development, which Marx also notably did before him, in which Marx envisioned the triumph of Communism over Capitalism to be the final development of mankind. As Yockey instead proposed an organic, living History that is constantly changing and evolving alongside our understanding of it, he naturally stands in opposition to the static, rationalized view of Fukuyama and Marx.

Yockey is by no means a well-known political ideologue, but he makes up for it in a multitude of ways. His unique developments of previous thinkers provide readers with many interesting ways to view History and Culture, which are concepts that they may now think upon in a different manner. While Yockey may provide an interesting way to approach Fascist philosophy for those who are already knowledgeable on the subject, he may prove difficult for beginners to fully process, which serves as his main weakness philosophically. But for those who are willing to work through what limited texts that are available, Yockey will certainly be able to provide them with a new way to approach politics, philosophy, and life itself.

Sources Used:

Yockey, Francis P. Imperium: The Philosophy of History and Politics. Invictus Books, 2011.

Imperium serves as Yockey's magnum opus, and as such is the culmination of all of his thoughts and ideals. In it, he examines many political concepts such as the nature of the State, Liberalism, and America. On top of this, Yockey develops his own theories such as the concept of a Culture-Distorter, as well as Culture-Parasitism. He compares his own philosophy to those that he considers his opposites, with the standouts being Marx, Darwin, and Freud. Throughout the book one can observe Spengler's influence on Yockey, who contrasts Spengler's own conservative beliefs with his own Fascist leanings, which provide a new and unique perspective on the previously mentioned ideas.

Yockey, Francis P. The World In Flames. III, Centennial Edition, 2020.

The World in Flames contains Yockey's shorter writings on various subjects at many points in his life, and as such grants the reader an interesting insight into how his worldview develops as his life progresses.

Mussolini, Benito. The Doctrine of Fascism. Enciclopedia Italiana, 1932.

As the only statement made officially by Benito Mussolini on the philosophical basis of Fascism, this short but informative document is invaluable for those seeking first-hand accounts on various aspects of Fascism.

Spengler, Oswald, and Charles Francis Atkinson. The Decline of the West. Arktos, 2021.

Oswald Spengler's flagship work, which thoroughly outlines his examination of many civilizations throughout history to observe what led to their rise and subsequent fall. His writings are important due to their contribution to various Conservative and Nationalist philosophers who came after him, as they were the first major use of the examination of history as a cycle, as well as Spengler's love-hate relationship with Hegelian dialectics. Yockey is unique for being the most prominent Fascist to take inspiration from Spengler, albeit with his own spin on Spengler's theories.

[1] Francis P. Yockey Imperium

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Francis Parker Yockey, The World In Flames

[7] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West

[8] Francis P. Yockey, The World In Flames

[9] Benito Mussolini, The Doctrine of Fascism

[10] Francis P. Yockey, The World In Flames

Recently I red your text on Jockey. It was great! For me it is quite surprising to know someone who study FP Jockey. In Spain, Imperium was translated into Spanish at the beginning of 70’s by the revisionist historian Joaquin Bochaca. That is why Jockey is relatively known in alternative circles. Thanks for your contribution.

He was an intelligent and honest man. He could not tolerate cruelty and lack of justice in Nuremberg trials. He paid all this with his life